"Meguru Monasashi" is an interview with people connected to Monosus about their own "yardsticks". This time, we have video director Yuka Oikawa. She started her career as a program production assistant for NHK during her student days, and after working as a director for BS2's "Midnight Kingdom", she has been working as a freelancer since 2009.

The connection between Oikawa and Monosus is that Yuka Hatanaka has asked her to produce videos centered around interview footage. Hatanaka, who has mainly worked on directing paper products in her career so far and is an amateur when it comes to video, says she has learned a lot from Oikawa's work on site.

The two recently spent time together on location in Singapore, which Hatanaka described as "quite tough." Hatanaka once again felt a strong connection between them that went beyond the relationship of requesting work and being requested to do it.

We will be delivering this interview, which explores Oikawa's roots, in two parts.

(Interviewer: Kensaku Saguchi)

Profile of Yuka Oikawa :

Video Director During his student days, he (inadvertently) got involved in part-time work in the video industry as a production assistant. In 1994, he started full-time TV program production as a director at NHK-BS2. He was thoroughly trained in the know-how of structuring, directing, shooting, and editing. Since 2009, he has been working as a freelancer. He is involved in jobs that "preserve things on video" regardless of category, from corporate VPs to contemporary dance video production and music videos.

The rain that had been falling until just before suddenly cleared up for just a moment. The supernatural powers displayed during the location shoot in Singapore

Hatanaka : Thank you for your hard work on the location shoot in Singapore. The pictures that Yuuka took were wonderful, and what's more, your sunny-girl power was amazing. It was raining lightly when we arrived at the airport in Singapore during the rainy season, and I thought it might be impossible to shoot outside at the port... but it cleared up just during the time of the location shoot! And then, the moment the shoot ended, a downpour started (laughs).

Oikawa-san jokingly said, "It's the director's job to make bad weather clear during outdoor location shoots!", but it really did clear up. What's more, it started raining again as soon as they finished filming.

Hatanaka : That was very moving.

Even Oikawa-san may have only experienced such a sudden clearing of the rain three times, including his time at NHK. I think the desire to create something great together got through to him.

Hatanaka: I've only had contact with you as a freelance video director, Yuuka-san, but before you went freelance you were a director at NHK, right?

Oikawa

I started working as a director for NHK's BS2 program when I was 23, quit after a little over 14 years, and became a freelancer, so this is my ninth year now.

Hatanaka: How did you end up becoming a director at NHK in the first place?

After moving to Tokyo, Oikawa attended an art school and started making stop-motion animation works on 16mm film, but developing the film was really expensive.

When I reached a point where I couldn't make it without a part-time job, I was introduced to a production assistant position at NHK. The daily wage was really good. 8,000 yen at the time.

At first I was drawn to the money, but then I found there were so many things on the TV set that I had never seen before. Before I knew it, it was more fun than going to school.

There were a lot of adults with good antenna sensitivity, there was equipment I had never touched before, and there were so many things I didn't know about what would happen on the scene, it was so much fun... Before I knew it, I had been working part-time for almost three years, and one day the director said to me, "I think you have talent, so why don't you try it full-time?"

Hatanaka: That was the trigger.

Oikawa: That's right. However, I don't have much patience, so I honestly asked, "If I think it's no good after all, is it okay to quit after a month?" and the director said, "That's okay." So I thought, "Let's give it a try," and since I'm a very competitive person, I was able to jump in.

Memories of my time as a new director, where I learned how to shoot and write narration on-site and was blessed with the support of my senior colleagues

Hatanaka: When you first went to NHK, you weren't a cameraman or a director.

Oikawa-san was just a part-timer. But he was quite dexterous, so he made small props and was very useful. If we had officially asked an art director, it would have cost money to make them, but we could do it with our part-time wages (laughs).

From there, I was approached by the director. At that time, there were many directors who were not full-time employees but had contracts for each program, and I felt like I was contracted as a member of the team. Moreover, the first program I was involved in at BS2, "Midnight Kingdom," lasted for 10 years. I think I was lucky.

Hatanaka : As a director, did everything go smoothly from the beginning?

Oikawa-san, not at all.

For example, even when I go to a location, I don't know how to shoot. So the cameraman asks me, "What do you want to do?" and "How should I shoot?" Of course, it's not mean, it's natural, but I shrink back and say, "No... well..." and I get annoyed and say, "I can't shoot if you don't tell me anymore," and I get scared. I feel like I was trained through such exchanges.

Hatanaka Yuka also had a time like that...

Oikawa: Yes. In that program, the director wrote all the scripts for the narration that was added to the footage, but at first I was in charge of a corner that introduced a theatrical work in 30 seconds, and in that short time I had to create a structure that summarized the beginning, development, twist, and conclusion, and only let people hear a few lines.

But I've never learned how to write, so I can't write. I often have to go through the course until the morning without being able to put it all together. But there's always one senior with me, and he's always there, looking at the magazine "Pia" in the editing room, and waiting for me at a distance, like "I'm not looking at all."

So when I showed them the finished sentence, they said, "I don't understand this. What is it that you want to say most?" or "This is what I want to say," and they never corrected the sentence itself, but instead corrected the surrounding parts.

No matter how poorly written the manuscript was, if I said, "I don't want to delete this," NHK, a company that values the subjective views of its reporters, would revise it to make use of that. In this way, I was trained by my seniors and gradually became able to do it. I can only be grateful.

Hatanaka: When did you start filming yourself?

Oikawa-san was originally a director, and he started operating the camera due to the trend of the times. Sony and other companies came out with small video cameras that could take images suitable for broadcast, and to reduce production costs, he thought, "It would be good if the director operated the camera too."

At the time, production costs were about 150,000 yen per crew member per day. Since there were multiple crew members working on site every day, it added up to a considerable amount of money.

For example, if you want to broadcast information that someone had a live concert in Shimokitazawa, footage shot with two cameras and cut-and-cut footage will have a more realistic feel than footage shot with one camera. So, I thought, why not just have the director film it?

At first, most of the directors were complaining. Even though their salaries weren't increasing, the amount of work they had to do increased. So, everyone was reluctant to continue filming.

Hatanaka: That's what led to your current style. When I first saw Yuka's style, I was surprised. I thought, "She's filming while doing the interview!" What kind of program were you involved in as a director at that time?

Oikawa

It was a program dealing with subculture that was an experimental attempt for NHK. BS2 had just started broadcasting, and at the beginning, it was a free forum where they could structure the program however they wanted for about three hours.

Each director will come up with a plan they want to do in a meeting, and it could be three one-hour programs, six 30-minute programs, or a 10-minute short segment. The programs deal with cutting-edge topics such as art, stage, and music. People who are interested and interested will find it interesting. We interviewed such subcultures and the people who are working hard on them, and put them on the air.

Hatanaka: That sounds really interesting.

I think it would be Oikawa-san . It may be a waste of time from a general value perspective, but there's no doubt that I was in touch with the cutting edge of the times, and I found it interesting to be on the scene. Before I knew it, I'd been doing it for 14 years.

Watching it on TV during your lunch break with excitement...

Why is this happening in the evening? My childhood experiences with digital divide

Hatanaka: Have you been into subculture since you were a child?

Oikawa: I'm originally from Iwate Prefecture, and my parents ran a pharmacy. I was the eldest daughter, so I really had to take over the business. I was a science student right up until my third year of high school, but when it came time to decide on my career path, all the things I'd been suppressing just exploded.

Originally, I loved drawing, so I declared to my parents that I would not take over the family business and that I wanted to do something related to art, but they were very against it. Nevertheless, I took the entrance exam for an art school and moved to Tokyo when I was about 18 years old.

Hatanaka: It's a powerful story that is relevant to this day.

Even for Oikawa-san , my father didn't voice much opposition... I wondered why, and later I found out that my father used to be a still photographer for a publishing company in Tokyo. He was forced to return to his hometown because there was no one to take over the family business, and he married my mother, who was a pharmacist, through an arranged marriage.

It's true that we had a developing lab at home. But I had never heard anything about photography from my father. Then one day, while I was cleaning up the funeral portraits of my grandparents, I noticed that the black-and-white photos had been retouched by hand. My father had taken all the photos and printed them. That's when I realized he had done it.

That's why I think he didn't say much about me wanting to study art.

I guess Hatanaka really does look alike.

Oikawa-san, I guess? I think my father really thought it would be good for me to take over the store, but, well,

It was a nice little story from our family.

Hatanaka : There are so many things I don't know.

Oikawa-san, you don't talk about things like this on the set.

However, her mother was against her even when she started working at NHK. Looking back, her reasoning seems reasonable, but back then there were no cell phones. So she would complain, "I can't get in touch with her whenever I call, and she's never at home. I don't know what she's doing," and "My daughter is doing a job I don't understand, and she's not getting married."

Hatanaka : By the way, has the day come when your mother is convinced?

Oikawa

This also ties into why I have continued to be involved in video. One day, I explained to my mother that "there are interesting things and interesting people out there, and I work to communicate that." "It's a job that communicates something that money can't buy," and she understood.

Yes, I was getting paid for my job, but to me it felt like I was doing something I wanted to experience and I just happened to be getting paid for it.

Hatanaka: A job that communicates something that money can't buy...I'd like to hear more about it.

Mr. Oikawa: When BS2 first started, and even after that, it wasn't a terrestrial channel. It was a channel that only select people could watch, and I think that was especially true before the internet became widespread, but I think that people in rural areas who were hungry for information watched it.

I was also from Iwate, so I was curious about what was going on in the city. This may be typical of rural areas, but at the time, there were only two commercial broadcasting stations in Iwate, and "Waratte Iitomo!" was on at around 4pm in the evening.

What I was wondering about was the song "Lunch break is fun watching~". "It's in the evening, so why is that?" Then my cousin said, "Why is it on in the evening? And I've seen this episode before," and it turned out that the broadcast itself was two months late.

But to my child's mind, it was a big deal and I felt like "what is normal is not normal!" When I asked adults why it was like that, no one could give me an answer, and when I told my friends, they didn't think it was strange.

Hatanaka: I said "During lunch break!" It's so like Yuuka to jump on it.

Oikawa: Because I have memories of that time, I think that at the root of it all is that "there should be no time lag in information, and I want to convey the correct information." Nowadays, with the spread of the Internet, there is probably no time lag in information even in rural areas, but at the time I thought it was sad.

Hatanaka: With that background in mind, you ended up on the side of delivering information.

Oikawa: Of course, I have had many encounters that have brought me to where I am today. I feel that I have been very blessed in that regard.

Taking a bath in the sink, crying while protesting at meetings - what keeps you going in a job that's not easy?

My name is Hatanaka , but I've been with NHK for 14 years. It must be hard to keep going for that long.

Oikawa: In my case, it might be my personality. I thought I wouldn't get results unless I kept at it. So I kept at it until the very end.

Hatanaka: What was the ratio of men to women on the production site at that time?

Oikawa: For example, out of a crew of 20 people, there are about 3 or 4 women.

Hatanaka: I don't really like to divide people by gender, but how did you overcome the challenges that are unique to women, like the physical aspects?

Oikawa: I don't think I had much trouble being a woman.

When I was 25 or 26, I had the opportunity to do four 30-minute segments filmed in New York. Up until that point, I had only ever done 10-minute segments, but I really wanted to do it, so I raised my hand.

Although the location was finished safely, the rough edit was almost to the death. At that time, there was no video editing on a computer, so I had to borrow an editing room. As a result, I was practically living in the editing room. But I wanted to take a bath. But I didn't have time to go home.

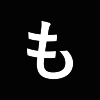

(Left) A New York location shoot he attempted in his mid-20s (Photo provided by art cocoon)

(Right) Gallery shoot in Tokyo

An interview with Daisuke Nakayama (left), an artist who Oikawa persuaded to do a location shoot in New York ("New Midnight Kingdom" special "Daisuke Meets NY", written and directed by Yuka Oikawa, NHK-BS2, broadcast 1999.2.15-2.18). Nakayama currently serves as the representative of the design studio daicon Co., Ltd. and president of Tohoku University of Art and Design, and continues to be in contact with him.

It's the Hatanaka dilemma.

Oikawa: So, I went in to try the sink.

Hatanaka : Wow, that really is an episode from the Showa era.

When Oikawa-san tried it, he thought, "Huh? Isn't it pretty deep?" He thought it was just a sink. Hot water came out, and you can buy shampoo at the convenience store. I think one of the reasons he continued was because he was able to do things like that without it being too much of a hassle. It's a fun memory. Looking back on it now.

Hatanaka : I wanted to keep editing until the last minute, so I chose to take a bath in the sink.

Mr. Oikawa: I don't know how to edit, so time just keeps passing by. But the deadline doesn't change, and I have to guarantee the quality to a certain extent. So I have no choice but to somehow squeeze in the time.

In fact, there is no doubt that the workplace is a tough environment for women. But I guess it's no good for both men and women if the hard times aren't enjoyable.

Did you have your own way of dealing with difficult times?

Oikawa-san, maybe it wasn't just a job.

I have never once thought about wanting to make a movie, and I have almost nothing to express from my own perspective. I think it would be good to play the role of conveying people, things, and things that I find interesting from my perspective.

At that time, artists and people working in contemporary art were making things that were really hard to understand, but there was a meaning behind them. The artist himself said, "Just look at my work," but there must be some parts that can't be conveyed unless he puts his intentions into words.

Even if there are various explanations and critiques in magazines like "Bijutsu Techo," I think it would be easier for viewers to understand if the creator himself spoke about it in a video, even if it was just for 30 seconds. So, it was interesting to go and shoot the work, ask the artists who tend to be reticent, "How about this part?" and have them talk about it.

So I think it was more fun than it was hard.

Hatanaka's suffering wasn't painful.

There were many times when it was tough for Oikawa-san . Like when she cried and protested in a meeting during a discussion about the direction and staging. However, I thought it would be a mistake to show my weakness as a woman. Because I thought that if I couldn't win, I'd lose. It's like a fight.

I hope that through the video I made, people in Iwate who, like me, were feeling like they weren't getting any information will think, "This guy is amazing!" or "This work is amazing!" and remember him for a moment.

Unlike DVDs or other packaged products, TV programs only remain in memory. Even so, if they can remain in someone's memory, that would be a wonderful thing. I think that's what I was thinking when I was doing it.

(To be continued in the second part)