こんにちは。編集部の大村です。

昨年の年末から東京に移り住んで約3ヶ月。まだどこか、旅をしているような気持ちが抜けずに東京で暮らしています。

東京で驚くのは朝の電車の混み具合もですが、美術展などの展覧会の圧倒的な多さ。駅にはたくさんの気になるポスターが貼ってあり、ついつい見入ってしまいます。

そんななか、行ってみたくなったのが世田谷美術館で開催中の「花森安治の仕事 デザインする手、編集長の眼」です。

戦後すぐに創刊され、約70年の歴史を持つ雑誌、『暮らしの手帖』の初代編集長が花森安治さん。手芸や工作、料理のレシピや著名人の暮らしにまつわるエッセイなどを掲載する、現在もつづく雑誌です。

花森さんは、創刊して亡くなるまでの約30年間、取材から記事の執筆、レイアウト、校正、カット絵、表紙画、そして広告まで。雑誌のほぼすべてに、徹底した信念と美意識をもって携わったという方。

花森さんの『暮らしの手帖』での仕事を紹介する展示はこれまでも何度か開催されてきたということですが、今回は雑誌の創刊以前や、雑誌以外の仕事も紹介し、ひとりの人としての仕事を知ることができる展示です。

編集という仕事に関わることになり、何か学ぶものがあればという思いと、美術館が素敵な場所にあるというお話も聞き、出かけてみることにしました。

世田谷美術館への道

2月末の良いお天気の日。美術館の最寄り駅、用賀駅に到着すると、早速、世田谷美術館を目指します。駅をでたところから、舗装された道が続きます。黒い石畳かと思いきや、用賀プロムナード(いからみち)と言うようで、瓦の素材で作られた道です。

用賀プロムナード(いからみち)

象設計集団さんが約30年前に設計されたというこのプロムナード。タヌキの形の水道があったり、絵本のなかの王様と女王様が座るような椅子があったりと、遊び心あふれるデザインです。

「お母さん、今日は水がないね」という子どもの声が聞こえましたが、小川のようなものもあり、夏には子どもたちの遊び場にもなっているのかもしれません。

プロムナードは住宅街のなかへと続いていくのですが、畑や梅の花が植えられている場所もあります。と、気になる看板を発見。

表示の通りにすすむと、

ここの畑で作ったという夏みかんやふきのとう、梅干しを地元の方が販売していました。ついつい、夏みかんとふきのとうを買ってしまいました。都内にもこんな場所があるんですね。

プロムナードを抜けると、砧公園へ。木が風でサワサワという音を久しぶりに聞いた気がします。

そして公園のなかにある美術館へ。ようやく到着しました。

世田谷美術館

「花森安治の仕事 デザインする手、編集長の眼」展

展示のはじめは、『あいうえお・もの図鑑』。『暮らしの手帖』にゆかりある品々をあいうえお順に紹介しています。

その後は花森さんの学生時代や戦時下の仕事を紹介し、『暮らしの手帖』創刊後は当時の誌面をパネルなどにして展示しています。今回の展示の特徴とも言える『暮らしの手帖』以外の本の装幀や、他社の雑誌の表紙画や広告も見ることができます。

盛りだくさんの今回の展示。7つに分けてご紹介します。

少し長くなりますが、ご興味のある方はお付き合いください。

1. 戦争体験を経て、雑誌づくりの道へ

花森さんは1911年(明治44年)に貿易商の父の元、神戸に生まれました。子どもの頃から宝塚歌劇や映画に連れていってもらい、絵が得意な子だったようです。詩や小説を書いていた学生時代には、新聞記者か編集者になるという夢をもち、東京帝国大学時代には学生新聞の編集者として活躍します。

大学卒業後、第二次世界大戦がはじまります。この頃から既に暮らしを工夫する本を作っていますが、驚いたのは、国策の宣伝機関でポスターなどのレイアウトに携わっていたこと。「欲しがりません勝つまでは」などのポスター制作に関わっていたようです。

そういった仕事の傍、満州などの戦地へも赴いています。戦時中に使っていた花森さんの手帖も展示されていますが、花森さんはその頃のことを戦後もあまり話さなかったそうです。

一方、学生時代から洋服への関心が高く、戦後すぐはイラストレーターや服飾評論家として活躍。『暮らしの手帖』の前身である『スタイルブック』を創刊します。たとえ新しい布がなくとも、着物や浴衣の生地を活用して洋服を作ろう、と「直線截ち」の技法を広めていきます。

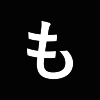

花森安治(1948)「素直な線の美しさ」、『スタイルブック 夏 1948』、p3~4、衣裳研究所

スタイルブックの創刊号。並んで人が買うほど人気だったとか。カラフルな絵や、身近にあるもので工夫して生活を変化させることができるという希望は、戦後すぐの物のない日々、女性たちの心を一気に華やかな気持ちにさせたのだろうな、と想像が膨らみます。

2. 「暮らしの手帖」創刊。大事にしたのは生活者の目線

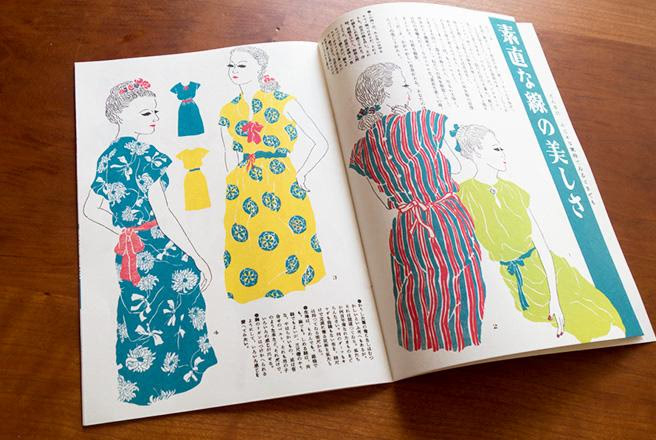

1948年(昭和23年)、もう二度と恐ろしい戦争をしない世の中にしていくための雑誌をつくる、と『美しい暮らしの手帖』(のちの『暮らしの手帖』)を創刊します。その頃、「暮らし」という言葉は暗いイメージがあったため、美しいをつけたということです。衣食住をテーマに、アイデアと工夫で楽しく豊かになる暮らしを次々と提案します。

パネルで展示される記事で、一番見ていて楽しかったのは「ソース家の物語」。1954年(昭和29年)の記事ですが、当時では珍しい、フランス料理の4つのソースを姉妹に見立て、カラフルなイラストで紹介しています。生活が豊かになるアイデアを楽しく届けたい、という思いが伝わってきて、この記事が掲載された号が欲しくなります。

暮らしに役立つ情報を載せる一方、社会問題を掘り下げる記事も。当時の保育所の問題や、公害など、経済が急激に発展する中で起こる問題に対して、あくまでも日々を暮らす「生活者」の立場に立った目線で問題提起します。

花森さん自身の、政治や経済に対する考えを綴った文章も展示されいますが、力強い文章に圧倒されます。

花森さんの記事を読んでいて思うのは、はっきりとした強い言葉を使われている文でも、すぐ横で語りかけられているような、不思議な感覚になることです。最初の一文から、ぐっと引き込まれ、いつのまにかどんどん読んでしまう。読者と同じ目線で「わかりやすく伝える」ことを常に意識していたのだそうです。

3. 153冊、すべての表紙画も手がけた編集長

また、花森さんは創刊から亡くなる1978年(昭和53年)までの153冊、すべての表紙画を手がけました。時代によって絵の雰囲気が変化するのですが、共通するのは、どれもにあたたかみがあること。

戦後すぐは、少し夢のある暮らしが想像できるような部屋や街角など。60年代は野菜や果物を工夫して撮影。70年代は女性をモチーフに、のびのびとした絵を描いています。

1948年(昭和23年)、創刊した第一号の表紙画。新聞やポットや傘、「暮らし」が垣間見れるようなシーンです。

表紙の絵は、記事やレイアウトなど、すべての仕事が終わったあとに一人部屋に籠もって描いたとか。出来上がると編集部のスタッフに見せて反応を見て、あまり反応がよくないと静かに修正していたそうです。

記事を書いて、絵も書いてと、何故そこまで、と思ってしまいますが、元々イラストレーターとしても活躍していた花森さんにとって、どちらも手がけることは自然なことだったのかもしれません。雑誌の随所にあるカットも、ほのぼのする絵ばかりです。

4. 貫き通した「広告を掲載しない」という道

『あいうえお・もの図鑑』では、「みなさん物をたいせつに」という言葉とともに、花森さんが使用したカメラや録音機、インク瓶のほか、「商品テスト」という『暮らしの手帖』の名物企画で編集部がテストした品々が並びます。

「商品テスト」では、アイロンや洗濯機、ベビーカーなどさまざまなものをテストします。ミシンの場合、数種類のメーカーを同じ条件でどれぐらい縫うことができるかを検証するため、一年かけて合計1万キロを縫ってテスト。トースターのテストでは、食パンを4万3千88枚焼いたという、徹底ぶりです。

今でこそ日本製の品質は高いですが、戦後は品質にばらつきがあったようで、公平にテストすることで、メーカーに対して良いものをつくって欲しい、という花森さんの思いがありました。

また、このような企画ができるのも、『暮らしの手帖』が広告を掲載していないため。広告を載せないのは自由に発言するためでもありましたが、心をつくしてレイアウトした誌面に、他の人がつくったもので乱されたくない、という花森さんの美意識があったと言います。

商品とは別に「火事をテストする」という特集もあるのですが、本当にストーブを倒して火事を発生させて消火方法を検証しているのは驚きます。

5. 日々を必死に生きる人々へのまなざし

私が展示で一番心に残ったのは、「ある日本人の暮し」というルポ。戦後を必死に生きる名もない人々を丁寧に取材しています。展示では、当時は「かつぎや」と呼ばれた、戦争で夫を亡くし、女手ひとつで子どもたちを必死に育てる母親の姿を追ったものが紹介されています。

風呂敷に自分で作ったお米などをくるんで都内へ売りに行くのですが、後ろ姿を撮った写真には、その人が背負った人生の重みを感じさせます。

展示室の一室では、花森さんの肉声が聞こえる部屋があります。怒っているような声でちょっとびっくりするのですが、毎朝早く起きて競(せり)に向かう人を取材した暮らしの手帖の編集者に対して、写真で表現できていない部分を力をこめて話している声でした。

よく聞くと「この人の身になって、気持ちのうえでは抱きかかえるような気持ちで撮っているのか」と諭しています。それほどの気持ちで撮影していたのかと思うと、言葉の強さの奥にある、花森さんの思いの大きさを感じました。

展示室の最後、一緒に撮影してもよいコーナーで、花森さんの写真を撮影させてもらいました。『暮らしの手帳』がはじまってまもない頃、全国のデパートで『暮らしの手帖展』をした時の準備の様子です。展示室の全てのものも手書き、手作りだったようです。

6. 「ペンで『暮らし』を守る」という決意

このように、雑誌でありながら、消費を促すわけでもなく、あくまでも人々の「暮らし」を豊かにしたい、という願いがこめられた『暮らしの手帖』。雑誌としては特異なものです。どうしてこのような姿勢で雑誌作りをされたのか。そこには戦争を経験したことが大きくありました。

展示では、終戦の日、花森さんが茫然自失で東京の街を歩いたという文章が紹介されています。この日、花森さんは「人間の暮らし」は何者も犯してはならないものという考えに至ったと言います。

それまでは「暮らし」なんてものより、もっと大切な何かがあると思って生きてきたけれど、敗戦してみるとそんなものはなく、「暮らし」を犠牲にしてまで守ったり、戦ったりするものはなかった、と気づいたのだそうです。

守るべき「暮らし」があればもう戦争はおきない。だから「暮らし」をペンで守る。その決意が『暮らしの手帖』を支えてきたのです。

7. 「戦争中の暮らしの記録」から生まれた、庶民の意思のシンボル

戦後22年たった1968年(昭和43年)、花森さんは読者へ戦争中の暮らしを書いてもらうよう呼びかけます。戦争の経過や指導者については記録が残されるけれど、戦渦を生きた人たちがどのように暮らし、亡くなり、生き延びたか。そんな記録が残されていないと思ったためです。

1736篇の応募があり、どれもが「書かずにはいられない」という衝動から書かれた文章だったといいます。そのなかから136篇を選び、『戦争中の暮らしの記録」として特集号を作ります。この号は後に本となり、現在も販売されています。

展示の終盤、つぎはぎの大きな旗が天井に掲げられていました。「一戔五厘(※)の旗」と呼ばれ、ある日突然、花森さんが作りはじめ、社屋にも掲げられていたそうです。

※「一戔五厘」とは、戦時中に兵士として召集されたときのハガキ一枚の値段。花森さんが出征中に、軍曹から「代わりは一戔五厘でくる」と言われて唖然となったことから来ているそうです。

つぎはぎの旗は、戦争中の暮らしを募った際に、何度も何度も縫い足したふろしきを使っていた、というエピソードからきています。

「一戔五厘=庶民」の意思の表明のシンボルとしての旗。その旗の下に、花森さんの「大きな力に屈しない」という思いがこもった言葉が並んでいました。

世の中を照らす灯火だった花森さん

今回の展示を通して、戦争を経験した花森さんだからこそ、並々ならぬ「暮らし」への思いが貫かれた『暮らしの手帖』が作られていたことがわかりました。

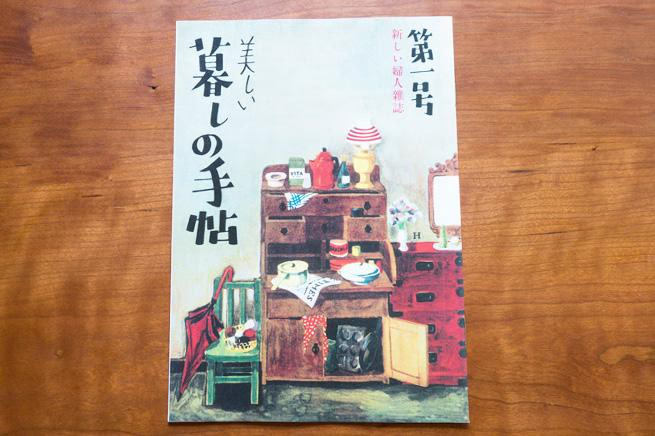

花森さんが好んで描いたモチーフの一つがランプ。「世の中を照らす灯火でありたい」という思いから、幾度となく表紙やカットで描かれています。

戦後をひたむきに生きる人たちや、隠れてしまいそうな問題にも光を当て、暮らしのアイデアを伝えることで人々の心を明るくする。一人で何人分もの仕事を果たした花森さんは、本当に世の中に光をもたらしたのだと思います。

私にとって『暮らしの手帖』は子どもの頃から家にあり、親しみのある雑誌でしたが、今回の展示を見るまで、ここまでの熱意で作られていた雑誌だとは知りませんでした。

美術館から帰って、久しぶりに『暮らしの手帖』を手にとって読んでみました。

表紙の裏には、いつもの文。

『暮らしの手帖別冊 暮らしの手帖初代編集長 花森安治』(2016)、p1、暮らしの手帖社

これは あなたの手帖です。

いろいろなことが ここには書きつけてある

この中の どれか 一つ二つは

すぐ今日 あなたの暮らしに役立ち

せめて どれか もう一つ二つは

すぐには役に立たないように見えても

やがて こころの底ふかく沈んで

いつか あなたの暮し方を変えてしまう

そんな ふうな

これは あなたの暮らしの手帖です。

(『暮らしの手帖』)

この言葉は花森さんのもの。

戦後、たくさんの方が『暮らしの手帖』を読み、自分の暮らしを少しずつ変化させ、その変化が回り回って、今の私たちの生活を潤わせてくれているのかもしれません。

私は、今年からものさすサイトの編集者としてスタートしました。

一つの会社のサイトではありますが、読んでいただいた人の気持ちが明るくなるような、そんなサイト作りをしていけたら、と思った日でもありました。

興味を持った方は、ぜひ美術館へ。過去の誌面をじっくりと見たくなるので、時間に余裕をもって行くことをおすすめします。(できれば、美術館への道も楽しんでください!)

美術館に行く道で買ったふきのとう。ほろ苦い春の味でした。

「花森安治の仕事 デザインする手、編集長の眼」

世田谷美術館

2017年2月11日〜4月9日

碧南市藤井達吉現代美術館

2017年4月18日〜5月21日

高岡市美術館

2017年6月16日〜7月30日

岩手県立美術館

2017年9月2日〜10月15日

展示が見られそうにない、という方は、こちらの本がおすすめです!

暮らしの手帖別冊 暮らしの手帖初代編集長 花森安治

(暮しの手帖社 2016 Amazon )

花森さんの表紙の絵やカット、装釘した本の原画などを見ることができます

花森安治(著)花森安治のデザイン

(暮しの手帖社 2011 Amazon )

戦争を生きた人々の「暮らし」をまとめた号が本になったものです

戦争中の暮しの記録―保存版

(暮しの手帖編集部 1969 Amazon )

花森さんが『暮らしの手帖』に執筆した文章の自選集

花森安治(著)一戔五厘の旗

(暮しの手帖社 1971 Amazon )

おまけ:娘さん、藍生さんのお話

後日、再び世田谷美術館を訪れました。花森さんのお嬢さんである、土井藍生さんのお話を聞く講演会があったためです。お洒落でハキハキとお話しされる、素敵な女性。

仕事とは別の、家庭での花森さんの色々なエピソードをお話してくださいました。

徹底したこだわりで雑誌作りをおこなったため、鬼編集長とも言われた花森さん。一風変わってはいますが、ご家族をとても大切にされていました。

娘さんの結婚式には職場からいつもの取材スタイルであるジャンパー姿でカメラと録音機をかかえ、式場の専属カメラマンそっちのけで撮影を続けたとか。ピントは花嫁である藍生さんにしか当たっていなかったそうです。

また、娘さんや奥様にもよく手紙を書いて送られていたようです。お孫さんへ当てた手紙が展示にもあるのですが、可愛らしい絵がたくさん描かれてあり、思わず笑顔になってしまいます。

仕事で日本中の人々の暮らしを変えることに全力を掲げた花森さん。自身の「暮らし」も大切にされていた姿を垣間見たようでした。