こんにちは、京都で暮らしているライター・杉本です。

フルフレックス&フルリモートで働く、モノサスメンバーのワークスタイル、会社に対する考え方や仕事観を聞くインタビューシリーズ「自由と責任 みんなの制度と働き方実験室」。わたしが取材・執筆を担当するようになってから、今回でちょうど10回目になります。

そんな節目にご登場いただくのは、神山サテライト・オフィスの本橋大輔さん。9月のある日、本橋さんがデスクを置く「神山バレー・サテライト・コンプレックス」を訪ねました。写真撮影は、ものさすサイト事務局に参加しているデザイナーの滝田怜子さんです。

光化学、バイオ、認知科学。傍らにはいつもコンピュータ

杉本:実は、ものさすサイトに本橋さんの記事が出るのは初めてなので、プロフィールから聞かせてください。

本橋:出身は埼玉です。10歳の頃に、父が中古でNECのPC-6001というホビーユースPCを買ってきて、コンピュータに夢中になりました。高校進学のとき、大きなコンピュータルームに惹かれて群馬高専を選びました。制服もないし、わりと自由にいろんなことができたんです。5年間の本科の後、2年間の専攻科に進んで学士資格を得ました。

杉本:群馬高専では何を学んでいたんですか?

本橋:化学です。昼は化学を学び、放課後は電算部(部活)でコンピュータルームに入り浸る生活でした。大学間のネットワークにアクセスしたり、「fj」というフォーラムに入って記事を読んだり。「Mosaic」という初期のブラウザに向けてviでHTMLを書いて、電産部のWebサイトをつくったりもしました。

杉本:専攻科ではどんな研究を?

本橋:本科5年生のときは化合物にレーザーを当てて、波長の変化を調べる光化学の研究をしました。専攻科ではバイオ系に寄って、環境浄化の研究をするようになり、その研究室では榛名湖で炭素繊維を沈めて水質を浄化する実験などをしていましたね。卒業後は、北陸先端大学大学院 知識科学研究科に進学しました。学生一人ひとりに広いブースと、WindowsPC、SPARC(サン・マイクロシステムズのワークステーション)が1台ずつ与えられて、自由に研究できると知って「最高だな!」と思ったんです。

研究科には、経済学や社会学、哲学など人文系の先生方もいて、なかでも面白かったのが認知科学を研究している先生。人間は、刺激に対してどんな反応をして、どう解釈して動くのかを分析するのですが、これはコンピュータと相性がいいと思い、その研究室に入りました。

杉本:光化学からバイオ、そして認知科学ってすごい振り幅ですね。本橋さんのなかには、何か内的なつながりがあるんですね。

本橋:コンピュータのなかでプログラミングして終わりにするのではなく、応用して何か別のことをしたいということですかね。

就職をきっかけに徳島へ、そして神山、モノサスへ

杉本:以前、ジャストシステムにおられたと聞きました。新卒入社ですか?

本橋:そうです。ジャストシステムは、大学のような自由な雰囲気のある会社で。オーナー企業だから自由がきくし、夜遅くまでみんながパソコンをいじっているし、大学の延長みたいでもありました。当時のジャストシステムは、自然言語処理(AI分野)の研究に力を入れていました。僕は、自然言語処理の研究はしてこなかったのですが、面白そうなので希望してその部署に配属してもらいました。

最初の3年くらいは、学生時代以上に勉強漬けでした。周りには、自然言語処理を一線でやってきた研究者たちがいて、みんな英語で勉強会をやっている。コンピューターを使った、本当に最先端の研究にいろいろ参加できてめちゃめちゃ面白かったです。ところが、入社9年目くらいに、キーエンスと資本・業務提携をしてから、ジャストシステムの経営体制はガラッと変わりました。これは僕にとってはつまんなくなるなと辞めて、世の中を広く見渡すことなく、向かいのビルに入っているモバイル向けのWeb会社に転職して、2〜3年働きました。

杉本:えっ? なんで、向かいのビルの会社に行くんですか……?

本橋:いやー、引っ越さなくていいかなーという感じで(笑)。部署異動の辞令を受けたとき、「ああ、そうですか」と自席に戻ってすぐ、用意していた履歴書を一斉送信したんです。一番早く返事をくれたのが、たまたま向かいのビルにある会社だった。僕はあまり、「そこに行こう」として移動はしていないです。結果的にここにいる、みたいな感じです。

杉本:なるほど……。じゃあ、神山に来たのもたまたま?

本橋:その頃、神山でサテライトワークの実証実験をしていた会社に、ジャストシステムの同期や先輩たちが何人か入っていて。「ちょっと興味ある?」と誘われて、遊びに行ったことがあったんです。その後、しばらくして声をかけられたのでその会社に転職して、2012年から神山に来ました。

杉本:ちなみに、モノサスには何年入社ですか?

本橋:2020年4月ですね。ちょうど同年1月に前職を辞めてフリーになっていて。「かま屋(フードハブのレストラン)」の中庭で焚き火を囲んでいるときに、真鍋さんから誘われたと記憶しています。入社してみて、フロント側のエンジニアはいるけれど、システム側のエンジニアがいないので、声をかけられたんだなと腑に落ちました。

本橋さん、なんでそんなに自由なんですか?

杉本:お話を聞いていると、自由でいられる場所を選んできていますよね。しかも、行った先でもかなり自由に仕事している感じがします。なんでそんなに自由なんですか?

本橋さんのワーキングスタイルはこんな感じ。奥に神山町の桜花連(阿波踊りの連)のうちわが見える。もちろん、本橋さんも踊ります

本橋:なんでですかね?逆に、みなさんは何にそんなに不自由を感じているのかわからないです。

杉本:自由にやっていくうえで、何に対して責任をもとうとするんでしょう。

本橋:エンジニアとしてはクライアントに対して責任を持ちますし、会社員としては会社の期待に対して責任を持っているつもりです。自分自身に対しては「いいものを作ろうとがんばる」というよりは、「こう組み合わせたら面白いものができそうだ」という感じが近いです。

杉本:ライターとしての自分に引きつけると、必死で文献を読みあさって原稿を書いたり、自分とまったく違う価値観の人に出会って話を聞くと、ちょっと自由になれる感じがあります。自分の枠組みが揺れたり、広がったりすることが、自由という感じに近いというか。

本橋:それは僕もなんとなく、似たような感じ方があります。できることがひとつ増えると、過去にできたこととの組み合わせで、またできることが増えるんです。増やせば増やすほどに、組み合わせがどんどん増えていくのはめっちゃ気持ちいいと思うことはありますね。

杉本:ライターは言葉を扱う仕事ですが、言葉は嘘をつくり、人を騙すことができます。だから、自分を問いつづけないといけないと思っていて。同じように、技術にも常にダークサイドがあると思います。本橋さんは、どんなふうに技術と付き合っていますか。

本橋:そのあたりは、群馬高専で受けたエンジニアリング教育がガードになっていると思います。エンジニアは新しい技術を誰でも扱えるようにするのが仕事で、それをどう使うかは倫理で縛ることだ、と。「pseudoscience(疑似科学)」を戒める、たしか「科学倫理」という名前の授業があったと記憶しています。エンジニアって新しいテクノロジーが出てくると、どんどん好奇心に従って動いてしまうんですよ。そのためにも「こうしてはいけないよ」という倫理による制御もあって、そのせめぎ合いもまた面白いです。

そもそも、誰かに害を与えるために自分の時間を使いたいとは思わない。特定の誰かに向けてものをつくるというのは、結果の対象が狭すぎますよね。それよりは、将来的な不特定多数のほうが、結果の範囲が広い。とは言いつつも、基本的には「こんなことを組み合わせたら新しいことができそう!」という好奇心でしか動いていないと思いますけどね。

顧客が求めるシステムを「引っ張り出して形にする」のが仕事

杉本:入社して2年、主にサイボウズ社「kintone」を用いたシステムをつくっているそうですね。kintoneを使いはじめたのは、なにがきっかけだったのでしょう。

本橋:はじめて触ったのは、2013年に参加したハッカソンで、電話回線を使ってタクシーを自動配車するシステムをつくったときです。KDDIの「Twilio(トゥイリオ)」という電話交換網APIから呼び出したデータを、kintone上でデータ管理するシステムでした。そんなことをしていたら、株式会社ソノリテから「kintoneの社内システムをつくりたい」とご相談をいただきました。

杉本:クライアントがほしいシステムをつくるときは、どんなふうに仕事を進めていますか。

本橋:基本的に、クライアントに「こういうものを作って欲しい」と言われたものが、本当に求められているものとは限らないと考えています。だから、クライアントの頭の中から理想的なシステムの姿を引っ張り出して、動くものにつくるのが僕の仕事です。なので、言われた通りのものをつくる仕事はやっていません。決まった設計図に従ってつくるほど、楽なことはありませんが、それはだいたいお金と時間の無駄になってしまう。少しずつ積み上げて、クライアントが本当に欲しいものにイメージを近づけていく方が、結果的に安上がりにもなります。

杉本:仕事以外でも、「神山メイカースペース」では3Dプリンタを使ったものづくりをしたり、ハッカソンに参加したり、いろんなものづくりをしていますよね。クライアントワークと個人でのものづくりに違いはありますか?

神山メイカースペース。最近新しい建物に移りました

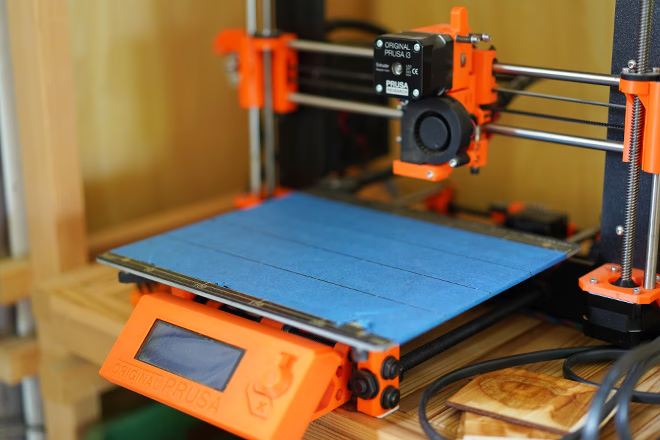

各種工具、レーザープリンタや3Dプリンタなどがあり、まちのものづくり拠点になっている。本橋さんは立ち上げ期からメンバーとして参加している

本橋:違わないですね。クライアントから相談を受けるとき、何らかの課題提示があるわけですよね。それを解決する仕組みをつくるわけですけれど、究極的に言えばそれも「自分で使ってみたいもの」なんですよ。

杉本:お仕事のなかで、一番うれしいポイントはどこにありますか。

本橋:つくりたいものを考えて、つくりはじめて動いたときですね。「あ、できた!動いた!」という瞬間の気持ちよさは、子どもの頃からずっと変わらないですよね。

杉本:コロナ禍もあり、他オフィスのメンバーと交流する機会が少なかったと思います。これから一緒にやってみたいことはありますか?

本橋:メンバーの誰が何をしているのかがわかれば、一緒にできることはたくさんあるはずだと思うんです。僕にできることはたくさんあるので、どれかで役に立ちたいと思っています。自分のもつスキルが役に立つってこんなにうれしいことはないですから。

神山メイカースペースでつくったオブジェについて楽しそうに教えてくれた本橋さん

「みなさんは何にそんなに不自由を感じているのかわからない」と言われたとき、びっくりすると同時に、すごく気持ちよかったです。本橋さんって、すごく自然な感じがします。「ナチュラル」というより「ありのまま」というか、思っていないことは言わない、とか。あたりまえのようで、あたりまえにできなくなっていることを、やりつづけている。それは、ひとつの才能なんだろうな、と思いました。

今度は、もう少し具体的に、本橋さんの仕事の内容を伝える記事を書けたらと思います。