プロデュース部 部長、 Food Hub Project 支配人の真鍋です。

先日、徳島にある民藝と暮らしのお店『遠近(をちこち)』のオーナーの東尾さんと、佐那河内村の建築家の島津さんと、兵庫や京都の器の作家さんや民藝のお店を訪ねる旅をしました。

その時の移動の車の中で、東尾さんが

器ひとつ作るにも、「外からつくる」作り方と、

「内からつくる」作り方とでは、出来上がるものは全然ちがうんです。

と話していたのが強く印象に残っています。

民藝の世界ではよく言われる話のようですが、その土地の素材で作ると、自然とその土地らしさが出てくる。徳島の大谷焼だったら土が軟らかいから自然とぽってりした形になる。一方で、海外で人気のある器を参考にして型を作り、うわぐすりをかけるように、その土地の伝統を上辺だけのストーリーとしてのせた器が世間的には売れている。そんな外からつくられたものを買う人たちにも問題があるけど、自分たちのような配り手にはもっと責任があると思う、と。

その時思ったのは、物づくりにおいては確かにその通りで、民藝と言われる器そのものは継承されている技術としての手仕事で「内から」つくられていて、昨今では、海外の考え方や見た目を日本に持ってきて「外から」表層的につくられたものが多いと感じます。(私たちの「Food Hub」という言葉や考え方も海外から持ってきているのもお忘れなくw)

でも疑問に思ったのは、民藝運動そのものは「外から」つくられているものじゃないかということです。

器においては「外から」つくるというのは少し否定的な話でしたが、民藝運動そのものを「外」からと「内」からつくるという視点でみたらどうなのか。また私たちフードハブの神山町での活動についてはどうなのか。それらを照らし合わせて、私なりの考えを書いてみたいと思います。

ちなみに、私は民藝の専門家ではありませんが、地域の農と食にまつわる、つくり手を応援する一人の活動家としてこの文章を書いています。(でも、ご指摘があれば何なりと。)

※メインビジュアルは、香川県東かがわ市にある陶芸家 上野 剛児さんの「火の谷窯」の工房での写真を使用させてもらっています。

外からつくる、内からつくる:

民藝運動と民藝品

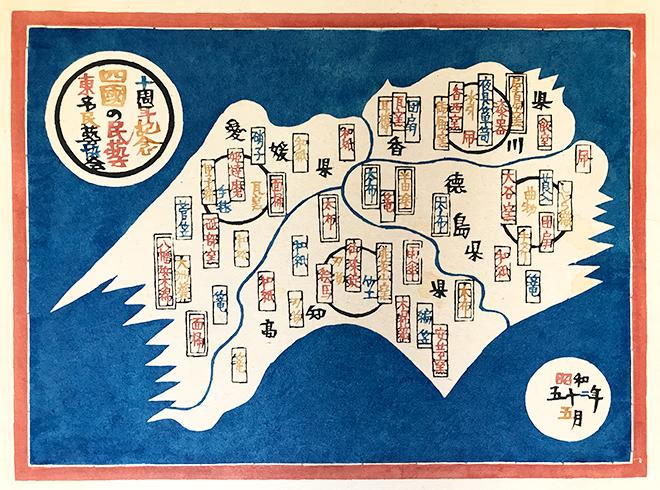

東尾さんのお店「遠近(をちこち)」のエントランスに飾られている、四国の民藝マップ。

民藝とは「民衆的工芸」の略語で、民藝運動は、1926年(大正15年)に柳宗悦・河井寛次郎・浜田庄司らによって提唱された生活文化運動です。(日本民藝協会ウェブサイトより)

私なりの見解ですが、民藝運動では「外から」と「内から」つくられるモノゴトが相互補完しながら、「民藝ブーム」といわれる世の中の浮き沈みを経験しつつ、現在の生活文化にも影響を与え続けている点が、個人的にはとても興味深いと思って見ています。

民藝運動は、その土地の素材や日々の生活の中で、無名のつくり手により生み出された生活道具にこそ本来の美しさ「用の美」が存在するという考え方を提示しました。それは当時の工芸界の「観賞用が主流」の作品に対して、地方にあるものを「外」からの視点でみて、新たな「美の見方」や「美の価値観」を提示したといえます。

では、この民藝運動とは、「外」からつくられたものでしょうか、「内」からつくられたものでしょうか。

当初、民藝運動とは距離をおいていた民俗学研究者の今和次郎が、面白い言葉を残しています。

1930年代の昭和東北大飢餓などで疲弊した農山村の生活改善事業の一環で柳が河井、浜田(民藝運動の中心人物)とともに東京視察をした際に、今和次郎が同行したことがあった。その際の今和次郎の回想があって「民藝の人たちはあくまで美的鑑賞の視点から入っている」と。一方で「我々は、現地の人の暮らしとか、生活をどうするかという観点から入っている」と。

鞍田崇・濱田琢司・伏見唯「民藝の”心地よさ”を探る」(「住宅建築」No.463 2017年6月号)75p

民藝運動は、美を追求するあまりに、矛盾をはらんだ活動とも指摘されています。

民藝には、合理化と機械化を推進したモダニズムによる大量生産、大量消費の社会や暮らしに対するアンチテーゼも背景にはあると私は理解していますが、今和次郎の指摘からも分かるように「民藝運動」そのものは、あくまでも工芸界の「観賞用」としての美に対するもう一つの選択肢として、すでに地域に存在した「手工芸」という美を、新たな価値観として提示しているにすぎないとも言えます。観賞という世界がなければ、生まれ出てこなかった美的価値なのかもしれません。

しかしながら、すでにあった価値に新たな見方を提示し、本来の価値を与える文脈づくりとして「外からつくる」大切な行為でもあったと私は思います。

それでは、民藝運動であつかわれる「民藝:手仕事」はどうでしょう。

柳宗悦は、物づくりに関して「材料でかたちをつくるんじゃなくて、材料がかたちをつくる」という言葉を残しています。

また柳は、日本的デザインとはどういうものか?という問に対して、「日本的デザイン?そういうものは、そこの土地で、そこの人が、そこの素材を使って、そこの人の生活の中でつくれば、自らそうなるもんでしょう」と言っています。

鞍田崇(編)フィルムアート社編集部(編)『〈民藝〉のレッスン つたなさの技法』 168p

柳たちが見出した「用の美」としての生活道具=民藝は、その土地の自然と生活様式から生まれでてくるもので、それは「内」からつくられている。つまり、「民藝」という言葉やその運動そのものは「外」からつくられているが、民藝として取り扱われる「器」などは、「内」からつくられていると言えるのではないでしょうか。

これらの「内」「外」と似たようなことばで、地方創生の文脈では「風土」という言葉を使って「風の人」「土の人」という話がよく出ます。ここまでの流れを踏まえて、私なりに定義すると以下のようになります。

・風の人:

その土地に新たな考え方や理想という名の風を呼び込み「外」からつくる人

(要素:風・雨・光など)

・土の人:

その土地に根付いていて、その土地で育て、受け継ぎ「内」からつくる人

(要素:土・種など)

ここでポイントとなるのは「つくる人」ということです。

「風の人」という言葉は、色々な地域を動き回って「関わる人」という意味で理想化され、よく使われているように思います。個人的にはあまり好きな表現ではないのですが、(お前も風の人じゃないか、というご指摘もあるかと)、民藝運動においては柳たちは「風の人」であると同時に「つくる人」でもあったと思います。

哲学者の鞍田崇さんが、著書『〈民藝〉のレッスン つたなさの技法』(フィルムアート社 2012年)の中で、柳の言葉を引用しています。

「美と生活とをひとつに結ぶことを努めたい。それは手近く私自身から出発せねばならない」(『私の念願』柳宗悦)。自らの言葉どおり、彼はただ古物を収集したわけではなく、衣食住全般にわたり、具体的な暮らしの型の提案を試みた。

「風の人」がもたらした新たな視点やつながりから「土の人(=無名の職人)」がつくる民藝の本来の価値が見出され、時に風の人と一緒に新たな物も生み出され、それがムーブメントとなった。つまり、その土地で長年受け継がれてきた種、そして耕されてきた「土」があり、そこに外から「風」が吹き、雨がふり、光が差し込むことで、様々なものごとが健やかに生え出てくるような風土が育まれていったのではないかと思います。

この関係性があるからこそ、今なお「風の人:外からつくる人」と「土の人:中からつくる人」が民藝に関わり、語り合うことで、現在も日本の生活文化に影響を与えて続けているのではないでしょうか。

外からつくる、内からつくる:

手工芸とプロダクト・デザイン

自宅で毎日使っている、砥部焼、日本の作家物、海外の作家物、工業製品のグラスなど。

また、今も民藝が影響を与え続けている理由は、もう一つ考えられます。

民藝運動そのものは、1950年代後半から70年代にかけた「民藝ブーム」を経験し、その流れで数多くの「民藝 “風” 」の物が生み出され、言葉そのものが古臭くなったり、運動も複雑化してしまい、徐々に世間の目が遠のいた時期があったようです。

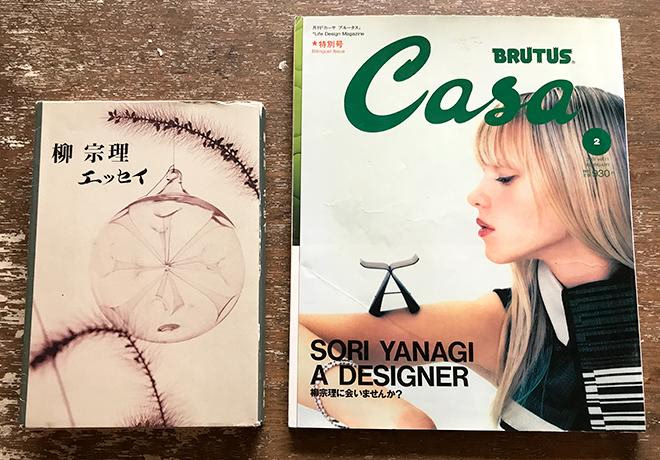

私は元々、プロダクト・デザイナーに憧れて大学でデザインを学んでいました。その後、デザイナーを諦めて(センスがなかった...汗)、デザイナーと一緒に働く仕事として広告の制作プロデューサーとして働きはじめました。その時代に、Casa BRUTUS などの雑誌で、柳宗悦の息子、柳宗理(やなぎ そうり)というプロダクト・デザイナーの特集などが組まれ、新たに起こりつつあった小さなブームから「民藝運動」を知りました。

2001年 2月に発刊された Casa BRUTUS vol.11 がまだ家の本棚にありました。日本民藝館を訪れる記事の中に、Food Hub Project の食堂「かま屋」をデザインしてくれた、Landscape Productsの代表の中原慎一郎さんが登場されていて、その若さにビビりましたw

柳宗理は、自身の書『柳宗理 エッセイ』(平凡社 2011年)にて、

手工芸は、手づくりの美しさを追求すべきで、プロダクト・デザインは、機械生産の美しさを追求すべきである。但し、人間生活に係わりあるものから、美が生まれてくるということで、その美の因って来ることは(民藝と)同じである。

民藝は、地域文化、或いは民族文化と言えようが、デザインは人類の文化である。

と書いています、また、父 宗悦と同様の表現でこう述べています。

日本人が日本の土地で、日本の今日の技術と、材料を使って、日本人の用途のために真摯にものを造れば、必然的に日本的な形態が出現することになる。この態度こそ日本の伝統の美しさを本当に継承することになるだろう。

このように、大量生産の工業製品が溢れかえり、価格競争の中で生きるこの時代に、民藝の解釈を現代のプロダクト・デザインという考え方にブリッジさせ、工業製品の中にも、用の美は存在するということを提示しています。

自宅で長年愛用している、柳宗理デザインのやかんやフライパン、ボールなど。

柳宗理は本の中で、彼の考える用の美を備えた工業製品をいくつも紹介していますが、最近の工業製品の中で、このような用の美を備えた製品はあるのでしょうか。

私が働いてきた広告業界は、ブランディングやマーケティング、プロモーションなどの手法を駆使し、メーカーがより多くの消費者に、たくさんの商品を売ることを手助けする業界です。その中で、商品を開発する時や売り方を考える時に、「マーケットイン」と「プロダクトアウト」という考え方があります。

マーケットインは、市場調査などを駆使し、顧客のニーズにあった商品をつくり出す、あるいは、顧客のニーズにあった売り方をすること。プロダクトアウトは、自社独自の技術などを活用しつくり出す商品のこと、もしくは、独自の技術を核とした売り方を言います。つまり、

- マーケットイン:外からつくる

- プロダクトアウト:内からつくる

と言えるのではないでしょうか。

大量生産、大量消費で物が飽和した時代に、この2つはもはや対局する概念ではなく、この2つの考え方がスパゲッティ状にごちゃっと入り乱れながら、用の美を備えない悪しきプロダクトが数多く生み出されているように感じます。

しかし一方で、日々の暮らしの課題や社会的課題を真摯に解決するために、「マーケットイン」と「プロダクトアウト」、「外からつくる」ことと「内からつくる」という2つの考えの間を振り子のように揺れ動き、既存の商品に対して現代のテクノロジーをかけ合わせ、新たな商品を生み出している企業もあると思います。

バルミューダというメーカーのトースターをご存知でしょうか。

私がこのトースターをここで取り上げるのは、天然酵母のパン屋の老舗『ルヴァン』のカフェのキッチンにこのトースターがポンと置いてあり(入手した経緯はともかくとして)、そのトースターが使い続けられていたからです。

これは「只物」ではない。と

この記事をここまで読んでくれた方々のどのくらいの人がこのトースタを持っているのか気になりますが(笑)、『バルミューダ』代表の寺尾玄さんと『ほぼ日』の糸井重里さんの『バルミューダのパンが焼けるまで。』という対談の記事のなかで、寺尾さんは「実は私、人びとはもう「もの」を買ってないんじゃないかと思います」と語っています。

さらに興味深い一節があるのでご紹介します。

みなさんが、お金を出して

「すばらしい体験」を買っているとすれば、

それを我々は提供したい。

ですから、五感すべてを使う体験、

すなわち「食べること」に

関わらなきゃいけないんじゃないか、と

思ったんです。

この後、糸井さんから、「‥‥‥それはきれいにつながりすぎてる(笑)!」と言うつっこみが入りますが、この一説は、先に述べた「外」からつくったという話、マーケットイン的な発想として捉えることができるのではないかと思います。

しかし、この記事を読む限りでは(実際にはどうかはわからないのですが)、最新のテクノロジーを駆使した工業製品をつくり出し、販売しているにもかかわらず、発想の原点や、物が作り上げられ、売られるそのプロセス全体が、日本の手工芸的な泥臭い方法で内側からつくられているように感じます。

内側から生まれてきている製品は、見た目にも機能的にも美しい。また誰もが共感できるようなストーリーも外側からも描かれている。『ほぼ日』での対談のように。

(ほぼ日の対談、ぜひお読みいただきたいです。)

つまり、今のような時代でも、あるいは、日本の大手家電メーカーが海外の会社に買収されるような今のような時代だからこそ、マーケットインとプロダクトアウトの両方の考え方を振り子のように行ったり、来たりすることで、手工芸的なプロダクト・デザインができるのではないかと思います。

生えてくるデザイン「考」

若いころに出会い影響を受け続けている本、お仕事でかかわらせてもらった本、最近強く影響を受けた本たち。

ここまでの話を整理してみます。

<民藝運動と民藝について>

風の人と土の人、外からつくる、内からつくるの関係性があったから、今も多くの人が民藝そのものに関わり続けることができ、その関係性が維持されることで、現在も多くの人に影響を与え続けてきているのでは。

<手工芸とプロダクト・デザインについて>

マーケットイン(外からつくる)とプロダクトアウト(内からつくる)のふたつの考え方の間を、振り子のように、行ったり、来たりすることで、外側と内側の両方から物事をつくり上げることで、生えてくるような手工芸的デザインが可能なのでは。

この2つの考えをベースに、

その1:

様々な雑誌などが食の特集を組み、数年前から起きている(と私は思っている)食ブームは、ブームとして終わらず、食を起点とした現代の「生活文化運動」として日本の食文化に新たな価値をもたらす可能性はあるのか。

→ 「生活文化運動」としてのフードハブを考える

その2:

グローバル化によって低価格化された大量生産、大量消費の食品業界と、料理人をスター化し、ガストロノミー的な星付けを行う高級レストランの業界。この両極化した食の現状に対して、無名の職人たちによる地域の「日常の食」は、新たな選択肢を多くの人にもたらすことができるのか。

→ 「日常の食」を生み出す、手工芸的デザインを考える

これら2つの視点から、次回は、私たちが神山町で始めた「フードハブ・プロジェクト」について考察しつつ、「生えてくるデザイン」について考えてみたいと思います。

(つづく)