プロデュース部 部長の真鍋です。

前回ご紹介した徳島県神山町の「Food Hub Project|地方創生と地産地食」ですが、先日、プロジェクトのメンバー達と、アメリカ西海岸のサンフランシスコ・ベイエリアに視察へ行ってきました。

今回の視察は、神山町が独自に取り組んでいる「スタディ・プログラム」として実施。

- 少人数(旅の質を上げる)

- 新しい組み合わせ(多様性をもたせる)

- 複数の報告会(色々な視点で幅広い層にくり返し行う)

プロジェクトメンバーでもある西村佳哲さん(リビングワールド)発案のプログラムで、ただの視察旅行で終わらないことを目的としています。

今回参加した「多様なメンバー」はこちら。

神山町役場の農業係、地域創生の戦略構築における主要メンバー(役場企画調整係、都市プランナー、プランナー・デザイナー)神山の農家さん、神山出身のライフスタイルショップオーナー、マーケティング・コンサルタント(弊社代表 林)、管理栄養士、コーディネーターの私の9名。本当に多様な視点を持ち合わせたメンバーで構成されています。中央の赤いTシャツの人はカリフォルニアの農家のジョーさんです。

なぜ、サンフランシスコ・ベイエリアだったのか?

あくまでも私見ですが、サンフランシスコ・ベイエリアは、バークレーにある Chez Panisse (シェ・パニース)という一軒のオーガニックレストランを中心に、40年の時を経て地産地食の文化とコミュニティが根ざす、とても特殊な場所だと思います。

そのレストランから多くの料理人が独立し、食にまつわる様々な事業を展開しています。競い合うのではなく、生産者を含めてお互いにつながり、協力しあうことで、地に足の着いた食文化が育まれている場所です。

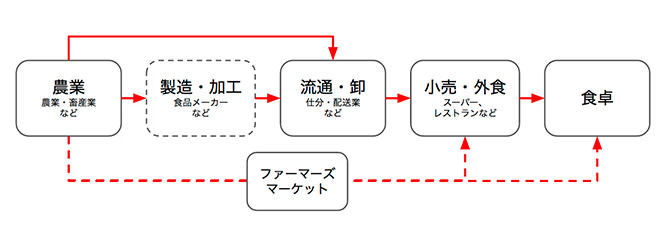

今回の旅で重要視したのは、Chez Panisse の元料理長 ジェローム・ワーグ氏に「旅の案内人」として協力してもらい、彼とともに農地を巡り、見て、聞いて、感じて、料理して、食べて、その文化の多くを身体に取り込むこと。加えて、フードチェーン(農業→加工→流通→販売→飲食)という食全体の流れを軸に、アメリカで浸透しつつある「フードハブ」の考え方を、実例から学ぶことを目的としました。

この記事では、視察したさまざまな出来事のなかから、フードチェーンの「農業」という部分にフォーカスして、独自のスタイルで農業を営む3名のお話を中心にご紹介したいと思います。

People's Plant & Nature Plant

人のための植物と、自然のための植物を育てる。

Bob Cannard / Green String Farm

ボブ・カナードさんは、理想とする農業を実践するために、ターキーの糞で畑としては使えなかった土地を借り、土壌を改善し、30年にわたり農業を続けています。収穫された野菜は、自社で経営する直売所と Chez Panisse との専属契約でのみ販売しています。

旅の案内人、ジェロームの計らいで、通常は入ることのできない"ホームガーデン"と呼ばれる彼の畑を見せてもらいました。Green String Farm Institution という若手農業家を育成する学校も開いているボブさんは、People's Plant(人のための植物) と Nature Plant(自然のための植物)の重要性について、熱く語ってくれました。

People's Plant チコリ(紫) Nature Plant クローバー(緑)

「 "人が食べる植物" を育てると同時に "自然が食べる植物" を育てるには、TIME、SPACE、 SHARING (時間とスペースを共有させること)が大事なんだ。最初に人が食べる植物を育て、遅れて自然が食べる(必要とする)植物を育てる。そして自然が食べる植物が畑の大部分を覆ってきた頃には、人が食べる植物の収穫が終わる。このサイクルが重要で、大切なのはオーガニック・マター(有機物質)をいかに土に還していくか、ということ。

現代の一般的な農法は、人が食べるものを効率的に育てることだけを考えていて、土の中の微生物が食べるものを育てない。だから微生物がいなくなり、土が痩せていってしまう。その結果、化学的なものを使わないといけなくなっているんだ。」

畑を凝視する白桃さん親子(父・神山農家、息子・神山町役場農業係)

神山農家の白桃茂さんは、「レンゲが生えていた昔の田んぼを思い出すね」と話し、その息子で役場の農業係の薫さんは、「畑じゃなくて花畑、カーデンやね」と話していました。ボブさんが「日本も昔はこんな畑だったはずだ」と言っていたのが、とても印象に残っています。

BACK-TO-THE-LAND

理想から入った農業で、世の中の問題に新しい選択肢を。

Joe Schirmer / Dirty Girl Produce

次に訪れたのは、Dirty Gril Produce という農場を経営するジョーさん。オークランドで大人気のラーメンレストラン "RAMEN SHOP" を経営する友人が紹介してくれました。

今回訪問したなかでは比較的規模が大きく、広い農場を案内してもらいながら、カバークロップという緑肥を活用した有機農業の話や、レストラン向けの野菜の育て方やビジネスの話などを伺いました。

様々な質問が飛び交うなかで、

「なぜ農業を始めたのか?」「農家の後継者問題はアメリカではどうなのか?」

という質問に、彼から興味深い話を聞きました。

「1960〜70年代に起こったヒッピームーブメントの頃に、"BACK-TO-THE- LAND MOVEMENT" という帰農ムーブメントが都市の若者の間で起こったんだ。これが最初の大きな動きだったと思う。もちろん農家の子供たちは、農業の厳しさを知っているので違う選択肢を選ぶことが多いのも事実だけど、最近では、大学で教育を受けた若者が、社会問題の解決や理想主義的な側面から農業に入ってきている。このベイエリアのコミュニティーには、食の社会課題に対するアクティビスト(行動主義者)も多いしね。

僕自身も、大学で学びながら社会的な問題について色々考え、結局のところ農業に行き着いた経緯がある。そして、インターンシップなどを通じてどんどん農業の中毒になっていったんだ(笑)。

世の中を見た時に、社会的な問題に対してサインを掲げて、指をさして叫ぶ方法もあるけど、僕は新しい物事をつくりだして、こんな方法もあるだろうと提示していきたいから農業をやっているんだ。自分自身が農業を継承していくことは大事だけど、それを自分の子供たちが受け継ぐかどうかは別に問題じゃない。」

ジョーさんは、40エーカー(東京ドーム約3.5個分、アメリカだと小規模)の農地を管理し、20人の働き手を雇い、レストラン向けに手間暇かけた作物をメインに育てています。近隣都市10ヵ所のファーマーズマーケットに出店し、最も単価と利益率が高いこの直販のマーケットで売上の60%を稼いでいます。ベイエリアでは料理人と同じように農家の人たちも非常に尊敬されている、と言っていたのが印象的でした。

No Input Farming.

自然農法で追求する、自分の生き方。

Kristyn Leach / Namu Farm

最後にご紹介するのは、Namu Farm を運営するクリスティン・リーチさん。

サンフランシスコにある大人気の韓国料理レストラン Namu Gaji と専属契約をして、自分がやりたい農業を追求しています。オークランドにある CAMINO などのレストランにも野菜を卸している関係で、CAMINO のシェフの奥様 アリソンさんが紹介してくれました。

農法について尋ねると「福岡正信の『わら一本の革命』は知っているか?」と話がはじまりました。

実は、カリフォルニアの Chez Paniss を中心とした有機農家さんやレストラン関係者から、よく同じことを聞かれます。福岡正信さんは愛媛県出身の自然農の実践者で、独自の理論と思想そして哲学を世界に伝えた人です。(1970年代にはカリフォルニアも訪れています。)現在は、お孫さんが彼の畑を継いでいて、私も数年前にジェロームと彼の畑を訪ねましたが、野山と果樹園が境目なく生息してとても美しい畑だったのを覚えています。

クリスティンの農法も、土作りに関してはこの畑で育ったもの以外はほとんど使わない自然農法。唯一、海苔を発酵させたものを肥料として、あとは緑肥(自然の草を土にすきこみ微生物に分解させて肥料にする)などで土作りをしています。トラクターや石油燃料を一切使わず、すべて手作業でかまや桑などを使って作業をしています。大きな機械よりも、壊れても修理しやすく、買い替えやすいもので作業する方が自分には合っている、と話していました。

この畑での作付けは5年目だそうですが、近年の雨不足でカリフォルニアの農業が苦しむなか、初年度の約3分の1の水量で同じ収穫量を確保できているそうです。(細かくログを取得しているとのこと)。また、オーガニックの種苗販売会社と契約して、様々なトライ&エラーを通して自家採種した種を卸すビジネスも展開していました。

専属契約している Namu Gaji や CAMINO は、Chez Panisse と同様に「旬の野菜で料理を作る」という考えが根底にあり、また農法についても理解があることで、双方の関係が成り立っているそうです。

聞くところによると収入は、日本の初任給程度で決して多くありませんが、新しい野菜の栽培や手間のかけ方など、自分自身が突き詰めたい実験的な農業が出来ることに、彼女は生きがいを感じていました。

「決して十分な収入ではないけれど、人生を通じてやりたい農法を突き詰める実験を続けていきたい。でも年をとったら、今ほどには身体が動かなくなるから、果樹園でもやろうかなと思っている。種の販売のように小さな収入源をいくつも組み合わせて、農業を続けていくことが将来的な理想よ。」

また、Food Hub のプロジェクトに対するコメントももらえたので紹介します。

「色々な立場の人が、一緒にこのプロジェクトに取り組もうとしていることは面白いわ。Food Hub の "農家を支援し地域の食を支える" という考え方はとても大切。この地域でもそんな場所を作ることを検討したけど、住宅や商業的な開発が進みすぎて、農地として確保できる土地が全く無いことがわかったの。近隣の食料自給率はとても低いのにも関わらず農地がないのは大問題。ぜひ今後もプロジェクトの進捗をやりとりしましょう。」

帰り際に「このレッドドライチリを持ってってよ!」と言われました。

聞くと、唐辛子は、料理人に人気で単価が高い上に、新鮮な状態でもドライでも、パウダーなどの加工でも、そして最後には種としても売れるからとても良いのだそう。「若い農家には、チリを育てな!といつも言ってるの」とクリスティン。独自の農業へのこだわりだけでなく、ビジネスセンスをも持ち合わせた彼女の考え方に深い魅力を感じました。

Farm Lifestyle and Social Farming.

農的暮らしと、社会的農業。

今回の視察を経て、「中山間地域の農を守る "農法" とは何か」をFood Hub Project のメンバーで議論しました。

そもそも農法を話す前に、「農」には、生業としての「農・業」と、生産性よりも自分の理想を追求し、自給自足に近い生活を極めていく「農的暮らし」があるのではないかという話がでました。この「農的暮らし」には、自分たちが食べるためや余った分を近所に配るようなことも含まれると思います。近年、田舎に移住して農業を始める人に多いスタイルですが、この「農的暮らし」が、これからの地方でとても大事な食文化の一端を担っていくことは間違いありません。

では、中山間地域の農を守るために、私たち Food Hub Project が取るべき方法はどんなものなのか。

今考えているのは、自然農法や有機栽培など「栽培方法の議論」に終始するのではなく、カリフォルニアで出会った農家さんたちのように「社会的な課題意識を持ちながら農業を営むこと」ではないかということです。

農業が町の自然環境を支え、地域の産業を支え、人の食卓を支えていることは言うまでもありません。そのなかで重要なのは、「なぜ食べるのか」を「なぜ農業をやるのか」につなぎ直すことだと思います。

そのために私たちが追求すべきことは、先述の「農的暮らし」の支援だけではなく、ボブさんや、ジョーさん、クリスティンさんのように「レストランなどのビジネスや、食べる人の意識に良い変化をもたらす農業」ではないかと考えています。

世の中の課題を意識した「社会的農業」という生業の在り方が、これからの中山間地域には必要なんじゃないか。今回のサンフランシスコ・ベイエリアへの旅をとおして、こんなことを強く感じました。

能書きばかりになってしまいましたが、いよいよ Food Hub Project も4月から本格的に始動します。私たちの正直な気持ちを、またこの場所からお伝えしていけたらと思っています。