こんにちは。編集長の中庭です。

モノサスに入社して5年ほど経ちますが、当初からずっと気になりつつも、社内の誰ともほぼ話題にしたことがないものがあります。

それはモノサスの入り口にある、「田山花袋終焉の地」の碑のこと。

入社当初は木造の碑で、鬱蒼と生い茂る草木のなかにひっそり佇んでいましたが、2年ほど前のある日、鉄製にリニューアル(?)。草木も刈られて、以前よりはっきりと視界に入ってくるようになりました。

しかし、木造だろうが鉄製だろうが、社内での注目度は低く、話題にのぼることはほとんどありません(一時Ingressで話題になった以外は)。

もしや「田山花袋って誰?はなぶくろ??」という人もいるのかも…。今回の「図書だより」では、田山花袋と代々木と私のおもいでについて書いてみたいと思います。

田山花袋のおもいで

田山花袋(たやまかたい)は明治4年から昭和5年を生きた自然主義派の文豪です。大学時代、文学部だった私は、2年生のプレゼミナールで彼の代表作『蒲団』についての小論文の課題を課されたことがありました。彼の終焉の地の碑を見る度に、当時のことと『蒲団』が思い出されます。

田山花袋『蒲団・重右衛門の最後』新潮文庫 1952年

『蒲団』のあらすじ

主人公は妻子ある30代半ばの中年文学作家。

作家志望で弟子入りを志願する女学生を自分の家で監督することになり、彼女に対して師弟愛とも男女の愛とも分からぬ感情を抱く。やがて女学生が同世代の男と恋仲になったことに嫉妬して、彼女を田舎の両親の元に返してしまう。主人公は、彼女のいなくなった部屋でひとり、彼女の蒲団にうずくまり、さめざめ泣く、というお話。

これは花袋自身の体験を元にした、私小説のはじまりとも言われる作品です(明治40年初出)。

話自体は、若い娘への中年の妄想。はじめて読んだ当時、特に共感するポイントはありませんでしたが、生ぬるい論文には容赦のないことで有名な先生(テクスト論で読む漱石研究家)の課題だったので、必死の思いで読みこんだことを記憶しています。(ちなみにその後、その先生のゼミに進むことに。そこで今の人生観の根っこの部分がつくられました。)

そんなわけで田山花袋には、ささやかな "おもいで” がありましたが、その後の日常生活の中で特におもいだすこともありませんでした。

しかしモノサスに入社して、彼の終焉の地の碑を見るたびに、「そういえば・・・」と頻繁に『蒲団』とゼミのことをおもいだすこととなったのです。

田山花袋と代々木

田山花袋が『蒲団』で描いた、中年男性が若い娘に妄想を爆発させる、という物語の傾向は、その数ケ月前に発表された『少女病』という作品からすでに始まっていました。

モノサス最寄りの代々木駅も登場する小説ですので、「代々木」つながりで、こちらもご紹介したいと思います。

『少女病』あらすじ

主人公は雑誌編集者の37歳、妻子持ち(『蒲団』と同じく花袋自身をモデルにした人物)。若い頃 "少女小説" なる新体詩のようなものを書いていた彼は、自宅近くの代々木駅から職場の神田まで通勤電車に乗る間、どの駅でどんな女学生が乗り込むか把握し、観察し、においを嗅ぎ、妄想するのを喜びとして、「ああ、自分に "美しい鳥を誘う羽翼(はね)" があれば!」と、嘆くお話。

ここまで書くと、花袋よ、大丈夫か?と言いたくなるくらい、身も蓋もない話ですが、そのキャッチーなタイトルのせいか、いまだに愛好家によって読まれ続けているようです。

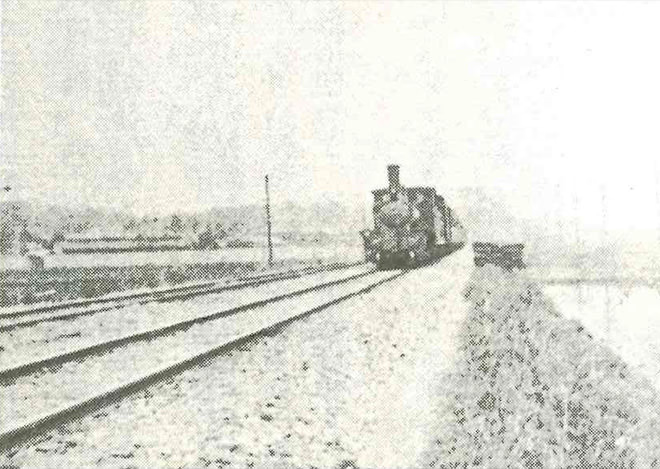

この小説は「甲武線」(今の総武線、当時は汽車)で代々木から御茶ノ水まで出たあと、「外堀線」(路面電車)に乗り換えて神田錦町の職場まで通勤するまでの経路がメインの舞台となっています。

当時(明治40年前後)の代々木駅周辺が、まだ「郊外」で、主人公の住む千駄ヶ谷の描写も田舎なので、読んでいて不思議な感じです。

渋谷・原宿間を走る蒸気機関車、甲武線(『渋谷区教育委員会発行『新・渋谷の文学』P114より)

郊外から都心まで通勤する主人公は、電車が都心に進むにつれて女学生のレベルがあがってゆくと観察しています。この郊外から都心の移動にともなう女学生の階層付けが、あたかも郊外/都心階層を表しているようだ、という解釈もあるようです。

(参照:石原千秋「郊外を切り裂く文学」『東京スタディーズ』P154以降 2005年初刊)

また、渋谷区郷土博物館・文学館の方のお話しによると、花袋の時代は、文学での立身出世を叶えようと上京したものの、挫折して帰郷していった夥しい数の若者たちが存在したとのこと。

彼らは明日の成功を夢見て、まだ地価の安かった渋谷に集まってきたそうです。

今は代々木から神田まで電車で移動しても、見える風景にそんなに違いはないなぁと思いつつ、かつての代々木フィルター(少女フィルターはひとまず置いておこう)をとおして今の代々木を眺めると、いつもとは違う、新鮮な眺めが広がる気がします。

自然主義作家、田山花袋の終焉の地にあるモノサスの代々木オフィス。お越しの際は、花袋の小説なぞ片手にいらしていただけると、またご一興かもしれません。