軽井沢風越学園・校長の岩瀬直樹さん(通称「ゴリさん」)に聞く、モノサス代表・林さんのお悩み相談。[その1] [その2]では“自由”を基盤とした組織においてチーム力を上げていくためのノウハウについて、さまざまな角度から対話を重ねてきました。

最終回の今回は、子どもにも大人にも共通する“やりたいこと格差”の話題に。「自由にしていいよ」と言われてもできない、その原因と解決策に迫ります。

原体験を塗り替えるような体験が、

身体感覚化したものを解きほぐす。

林:モノサス(株式会社モノサス)とフードハブ(株式会社フードハブ・プロジェクト)というふたつの会社の代表を務めていて大きな違いを感じるのは、フードハブのように目的が明確なチームには、意志のはっきりした人じゃないとジョインしにくいという点です。社名にもプロジェクトと入っていますし。

でもモノサスは採用の時点で意志を問うてはいない。すると、自分のやりたいことをビジネスにしようとするときに、その一歩目のハードルがすごく高いんですよ。「やってみればいいじゃん」って言っても、彼らはまったくエンパワーされないんですよね。そこに寄り添うことの難しさを感じています。

岩瀬:何が一歩目のハードルを上げているんでしょうね。風越でも同じようなことが起きています。

林:「やりたいと思っていることはあるけど言えない」という人もいると思いますが、本当に突き詰めていくと、実はまだ「やりたい」に至ってない状態が、いまの30代以上には蔓延しているな、と思っていて。

池田:それは子どもにも起こることではないでしょうか?いきなり自分の探究に没頭できる子もいれば、なかなかやりたいことを見つけられない子もいるんじゃないかな、と思います。そういう子たちに対して、岩瀬さんはどう働きかけますか?

岩瀬:自由度の高い風越で起きていることって、“やりたいこと格差”なんですよ。やりたいことであふれるような子は全然時間が足りない。でもずっと時間を潰しているような子もやっぱりいます。僕も含めてスタッフは悩んだんですが、一番ダメだったのは「何やりたいの?」って聞くこと。これって本当に最悪の質問で。

林:ホントすいません……(笑)

岩瀬:「何やりたいの?」って聞くと、「え、工作かな……」って無理やりひねり出す。ですが、実は別にやりたくなかったと後でわかるみたいなことが頻発したんです。「本当にやりたいこと」は、ほじくり出そうと手を突っ込んでも痛いだけ。子どもは「やりたいことがない自分はダメなのかも……」みたいに思っちゃう。

だから、人やものにたくさん出会うしか無いと思っていて。そのなかでパチっとハマったものの中から、人は「やりたい」を見つけていくんですよね。やりたいことって、関係性の中から生まれてくるんです。

池田:“やりたいこと格差”は、出会う量の差から生まれるのでしょうか。その他にも原因が?

岩瀬:原体験の量も影響していると思います。たとえば「森のようちえん」出身者は本当にやりたいことを見つけるのがうまくて、何でもすぐ楽しみにして没頭しちゃうんです。小さい頃から、面白そうと思ったことをとことんやれているか、という経験の差はあると思います。

だから学年が上がれば上がるほど見つけられない層が増えていく感じはしています。それは学校教育で、「やりたい」じゃなくて「やること」が時系列でやってくることに体が慣れていくから。30歳くらいの人は、そういう経験を積み重ねてきているから、というのが多分にあるんじゃないかと思いますね。

林:そうなんですよね、そこを解きほぐすのが難しくて。

池田:風越の先生たちはどうですか?

岩瀬:本当に人それぞれですね。そもそも自分の「楽しい」という感覚で動いている人は楽しみ上手だし、やっぱりちょっと管理者みたいな関わりになっちゃう人もいます。

池田:そういう人が変容する、みたいなこともありますか?

岩瀬:それは割と簡単に起こると思います。「子どもと走ってみてすごい楽しかった!」みたいな体験をすると、ぐっと体が変わるんですよね。

池田:体が変わる。

岩瀬:「授業は座って聞くものだ」みたいなものって、身体化しているんですよね。そういう人たちが「新しいことをやりたい」って動いても、うまくいかないと自分の馴染みのあるかたちに戻っていく。それで体が安心するんです。

それを変えていくには、原体験を塗り替えるような体験をすること。子どもの育ちに関わっている人はそういう可能性が高いと思います。常に子どもという最高のメンターが側にいるので。

人は集団の中でしか解放されない?

会社の役割と、学校の役割と。

林:僕、大学時代に男声合唱をやっていたんですが、声の癖を取り除くためにする一対一の発声トレーニングって、男同士なんですけど服を脱ぐのと同じような恥ずかしさがあるんです。目を見つめて「お前を受け止める」っていう信頼関係をつくってやるから、下手したら声と一緒に相手の性格の癖や、なんなら恋人と「きっとこんな会話している」ということまで入ってくる。

杉本:すごい、魂の移植ですね。

林:そう、本当にやりたいことを出すのもきっと似ていて、深く入り込んで一対一でやるか、グループの中でかなり時間をかけてやらないと難しいな、と。

池田:グループの中、ですか。

林:人って集団の中でしか解放されないんじゃないか、というのが僕の仮説としてあって、その機能が会社として持てるといいな、と思っているんです。

杉本:めっちゃ面白いですね。林さんが会社をつくって何をやりたいのか聞いてみたくなりました。

林:なんなんだろうなー。でもそういう意味では、大学のクラブが根底にあるのかもしれない。けっこう本格的なクラブで、自分たちで依頼演奏受けて稼ぎに行ったりもしたんですが、いがみ合ったりもするし、音楽経験のない奴らばっかりでやっているので本当に大変なんですよ。でも4年間やってるとみんな悟ったようになって、「ずっと一緒に生きて行けたらいいのに」と思うくらいの関係性になる。4年目は本当に“自由の相互承認”の場があるんですよ。

「大学は4年で終わっちゃうけど、これが会社でできたら死ぬまでやれるってことだよな」って思ったのが、たぶん会社づくりのスタートだったと思います。でもこれが難しいんですよ、仕事が紐づくと。

杉本:一番難しいことをやっているんだな、と思いました。

林:でもやっぱり会社の役割ってそこかな、と思っていて。いま地域に属しているという意識、もっと言えば国に属している意識もすごく薄くなってきている中で、会社がその対象になるといいなと思っているんです。

僕は会社って社会への入口だと思っています。個人では社会に参加するってところまで行けない人も、会社だったらできるんじゃないかな、って。だから「会社ってなんだろう?」というのが一つのテーマなんです。風越は「学校ってなんだろう?」っていう問いだと思いますが。

池田:岩瀬さんは、学校の役割はなんだと思っていますか?

岩瀬:学校の役割というか、風越で僕が追求しているのは、「幸せな子ども時代を過ごす場ってどういう場なんだろう?」という問いなんです。子どもって、起きている時間の大半を学校で過ごしますよね。必ずしも学校である必要はないんだけど、これをなくす作業はたぶん難しい。だけど、再定義はできるな、と思っていて。

たぶんその場は子どもだけでは成立しないだろうから、風越では子どもも保護者も一緒に考えて一緒につくるということをしています。でもまだ、見えている感じは全くないですね。なんとなくこっちの方向かな、というのはありますけど。

池田:なんとなくの方向、というのは?

岩瀬:ひとつは居心地がいいということ。もうひとつは、自分が変化しているという実感を本人が持てるかどうか。その2つがあると、人が育っていく場として面白くなっていくんじゃないかな、と思います。

林:変化は、何で大事なんですか?

岩瀬:人って、自分が変わっていくことがうれしいんじゃないかな、と思っていて。シンプルに何かができるようになったということ以外にも、面白いことが増えたとか、あの人との関係性が変わったとか、自分の中でそれが面白いと思える方向に変わっていっているというのは、人の幸せとつながっているんじゃないかと思っているんですよね。

林:それがみんなに当てはまるんじゃないかというのは、仮説ですか?

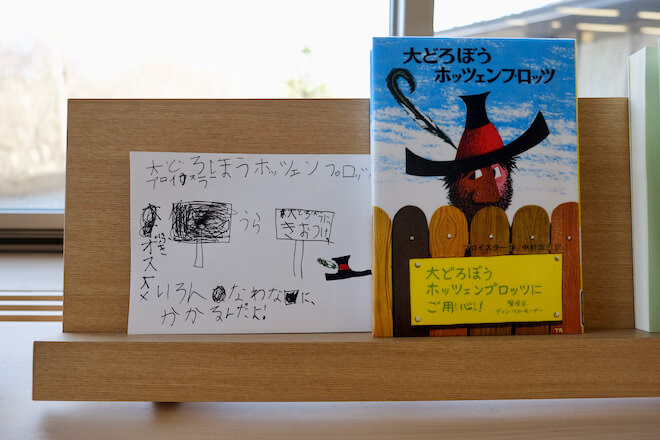

岩瀬:僕の中では仮説ですね。僕自身がそうなので。子どもたちも、たとえば、読める本が変わっていくってうれしいんですよね。絶対読めない本でも、眺めていたら「こういう世界が広がっていくんだなー」っていうのが想像できる。変わっていくことって、自分の可能性への信頼というか。

林:なるほど。なぜそんなことを聞いたかというと、大人になると変化そのものが嫌いな層が結構いるな、と思っていて。でも、年齢を積み重ねていくうちに体が凝り固まっちゃっただけで、本当はうれしいのかもしれませんね。確かに子どもはみんな喜んでいる。家に帰ったらテレビを見ていた娘たちが、最近ライブラリーで借りた本を読んでいるんですよね。年中の次女もいつのまにか字が読めるようになっていて、それがうれしいのか、黙々と本を読む姿をよく見るようになりました。

杉本:いいなー、子どもが本を抱えているのを見るとすごいうれしくなります。

岩瀬:うれしいですよね。

他人の関心に関心を……持てるのか!?

林:ドキュメンテーション、帰ったらすぐやりたいなと思うんですが、岩瀬さんは読んでいて楽しいですか?

岩瀬:楽しいですね。

池田:林さんは楽しめそうですか?

林:楽しめなさそうな気がして、自信がない(笑)。そこってなんで楽しいんですか?最初から楽しかった?

岩瀬:なんで楽しいんでしょうね……。僕は学級担任が長くて、クラスの子ども一人ひとりに起きていることにすごく関心があったんです。その子に関心があるという以上に、その子の関心に関心がある。ドキュメンテーションを読むとその人の関心が見えるから、ぐっと関わることが楽しくなるんですよね。

林:じゃあ、他人の関心に関心がない人間は、どうやったらいいんですかね?

池田:でも林さん、坂本さんとの交換日記では関心を持っていたのでは?

林:持っていた。そのときはスイッチを入れてやっていたから。

僕、社会人4年目のときに8人同時に交換日記をやっていたことがあって、そこで一人ひとりとつながった実感があったんですよね。つながりたかったのかもしれない。

岩瀬:交換日記そのものが相手の関心に関心を寄せるプロセスですからね。

杉本:つながるツールが、岩瀬さんにとってはドキュメンテーション、林さんにとっては交換日記。やっていることは同じなのかもしれない。

林:確かに。でも絶対やってくれないんだよなー。社内で一度提案したんですが、「やる意味わかりません」って言われて。

杉本:坂本さんは、リモートワークが始まってから、みんなに手紙を書くようにして、「週刊坂本ニュース」を発行しはじめましたよね。たぶんそれって、林さんとのやりとりで何かがインストールされていたからじゃないかな。

林:個人に対してはそうですけど、組織に対してインストールできていなんだろうな……。うーん。まだまだ相談したいことはいくらでもありますが、続きはまた。風越、通います!

(対談ここまで)

3本に渡るお2人の対談、いかがでしたでしょうか?

学校と会社、子どもと大人という違いを越えて、どんな組織・チームづくりにおいても普遍性のあるお話だったと思います。読んでくださったみなさんにとっても、それぞれに気づきの残る記事になっていたら、うれしいです。

「学校ってなんだろう?」「会社ってなんだろう?」と問い続け、自ら変化し続けるおふたりにとって、探究心あふれる子どもはまさに “最高のメンター”的存在なのでしょう。対談に同席した私自身も、「あ、だから私は子どもの育ちの場を取材し続けているんだ」と、改めて自分の中にあるエネルギーの源に触れた思いです。林さんと同じく、「通います!」と宣言したい気分(笑)。

名残惜しそうに岩瀬さんとの対談を終えた林さん、まずはモノサスでドキュメンテーションを試してみようと決心したようです。果たしてその成果は……?今後のモノサスの変化も、追い続けていきたいと思います。